The way a lifter sets up and controls his joints through the lift’s movement angles and positions can make or break the rep. Of all the joints to consider, the elbows are often overlooked. Not surprisingly, they’re all anyone would ever talk about only when they start to hurt. If you’re unlucky, an annoying elbow injury can affect all four lifts.

It’s easy to assume that the elbows are only important in upper body lifts, since they’re a major contributor to pressing movement patterns. But they matter just as much in the lower body lifts as well.

In my own training, my right elbow has been the most persistent source of discomfort, flaring up every now and again. It took a long time to heal, and even now, the discomfort can easily resurface if I’m not paying attention. Since then, I’ve been more mindful of what makes it feel better or worse during lifting. I’m glad to say I’ve recently been moving weights close to my heaviest for sets of threes and fives without any pain. The last time I was in this range, I remember approaching each weekly increase on the bar with some trepidation. Thankfully, experience has guided me to continue lifting heavier while keeping injuries at bay.

I may never know exactly what caused this particular elbow issue, but I’ve learned a lot about where the elbows should be and how they should, or shouldn’t, be used in the main lifts. Because we rely on our hands to interact with the bar, the elbows inevitably come into play — so here are some helpful ways to think about them as you lift.

Upper Body Lifts – The Weight Is in Your Elbows, Not Your Hands

In both pressing lifts, the most noticeable sensation is the “heaviness” felt in your grip. As the weights get heavier, some lifters instinctively try to jab the bar toward the ceiling with their hands in a last-ditch effort to finish a tough rep. “Just press the bar up!”—it sounds logical enough. After all, the bar is in your hands. But once the weight climbs high enough, shifting your focus to driving the bar from your elbows instead of your hands proves to be effective for many lifters.

At the bottom of either presses, think of your elbows as coiled springs, loaded and ready to generate upward force into lockout. The bar moves when the elbows and shoulders extend and straighten.

Your hands, on the other hand, are simply there to maintain a tight grip with neutral wrists—they are not the primary source of force. Maintaining that tightness in your wrists also helps to keep your forearms rigid through the movement upwards. When grinding a heavy rep to lockout, you don’t want any wrist extension to happen – that can add moment force that can put you ever so slightly out of form, adding moment force to your movement, and causing you to work unnecessarily harder, and possibly making you fail the rep. Thus, for both presses, think about pushing up from your elbows, bouncing off the tightened coils, instead of pushing from the bar in your hands.

Overhead Press – Set With Your Elbows, Move With Your Elbows

The elbows matter most in the overhead press at the very start of the movement. Viewed from the side, the point of your elbow—the olecranon process—should sit just slightly in front of the bar. From the front or back, the forearms should be vertical, directly underneath your fists. This setup gives you the best leverage to drive the bar overhead. As you press, imagine springing your elbows upward, keeping the bar balanced over the mid-foot as it travels toward lockout. When lowering the bar, bring it down under control. Avoid letting it crash or sink too low, which can cause your elbows to drop below the correct starting position and throw the next rep out of balance.

Bench Press – Lead With Your Elbows

The bench press is the only lift where a little mechanical inefficiency of a non-vertical bar path is introduced on purpose, in order to preserve shoulder health. And since we can’t change this unfortunate feature of the bench press, we will have to work hard to prevent any excess inefficiency through the journey down and up.

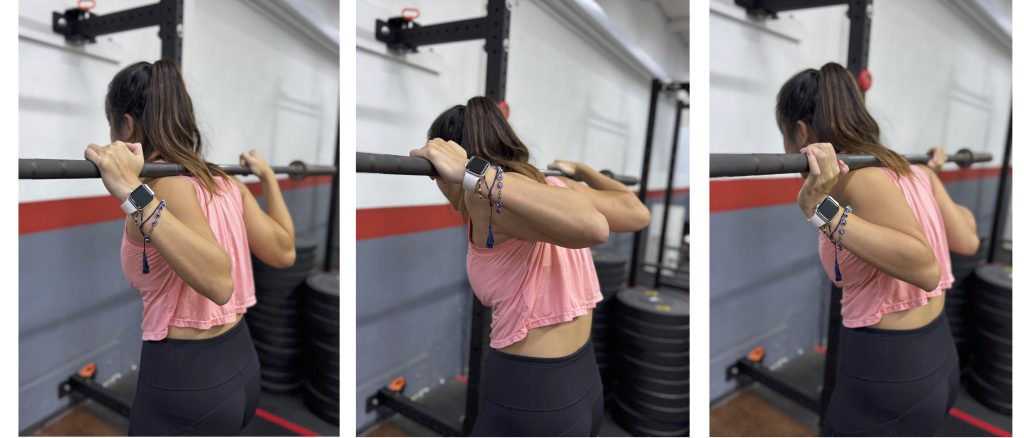

In the bench press, the goal is to arrive at the right position at the right time. The bottom position of the bench press shares some similarities like the start of the overhead press: the elbows should be slightly in front of the bar when viewed from the side, and the forearms should be vertical beneath the fists when seen from the front or back, as depicted in the left-most picture above. This is will be the most efficient bottom position for the bar to start driving back up from. Elbows and forearms that are in any other position would cause a much harder journey back up, due to added mechanical inefficiency to the already inefficient movement.

On the descent, imagine leading the bar down with your elbows. This mental cue helps maintain the correct path and keeps your arms in position for an efficient reversal of direction. When the bar touches your chest at the touch-point, your elbows—like coiled springs—will be perfectly positioned to help drive the bar back up using your loaded triceps. Shift your focus away from the bar and hands, use your elbows to lead the way down to the most efficient touch-point, and prepare to spring off back to the top in the same direction.

Lower Body Lifts – The Weight Must Not Be in Your Elbows

In squats and deadlifts, your elbows have no business bearing any of the load. Once they’re set in the right position, leave them alone. These are heavier lifts that rely on the muscle groups surrounding larger joints – hips and knees – to produce force to overcome the weight. These joints are significantly stronger than your shoulders and elbows, which means the weights used for squats and deadlifts will be much heavier than those used in pressing movements – far beyond what your elbows or shoulders are meant to handle.

Squat – The Elbows Stay Put

In the squat, the ideal elbow position comes from setting up with the following key features:

• Hands gripping the bar as narrowly as shoulder mobility allows

• Bar in contact with the fingers and the fleshy part of the palm, while keeping wrists neutral

• Bar pinned tightly under the spine of the scapulae, resting securely against the rear deltoids, which remain contracted throughout the movement

With these in mind, your elbows should stay that way in order to maintain these features of your set up. Cranking the elbows higher than needed cause your shoulders to extend too much, which may lead to the upper back rounding (thoracic flexion). If you allow the elbows to lower excessively, you risk losing the nicely contracted shelf for the bar to sit securely on, and in many cases, results in the elbow bearing some of the load which can cause a great deal of elbow discomfort if uncorrected. Elbow movement during the rep could cause an unstable interaction between the bar and the shelf on your back – a moving bar on your back can rock you out of balance.

Throughout the squat rep, from lockout to depth and back up again, the bar sits squarely on the “delts shelf”. At no point should you feel any weight in your hands, wrists, or elbows. It’s easy to ignore this sensation, but as the weight increases, what your hands and wrists can’t handle will be passed down into your elbows to bear, causing one of the most common squat-related elbow issues. If you are worried about feeling tension and some discomfort while setting up for the squat, don’t worry – it’s normal and should dissipate once you’ve racked the bar. What isn’t normal is lingering pain that worsens over time. In that case, get a coach or a well-informed individual to check and troubleshoot your grip and elbow positions for you before it turns into a chronic issue.

Deadlift – Hang Your Elbows

A common issue among new lifters is the tendency to “carry” the weight of the bar all the way to lockout, even maintaining bent elbows all the way to lockout. At lighter loads, the rep might still go up relatively effortlessly despite a slight bend in the elbows. If your elbows aren’t fully extended as the weights get heavier, it’ll get straightened out whether you want to or not – and that’s a recipe for injury, one that’s entirely preventable with proper setup and awareness.

As you set up for the deadlift—stance, grip, bend knees to the bar, chest up— and your elbow should be straight before you push the floor away with your feet. Straight elbows are critical for effective force transfer. They serve as rigid levers that transmit the force generated by your hip and knee extensors, through a rigid back and rigid arms, then finally into the bar to get it moving off the ground. Your arms should not be straightening by the force of your knees and hips extending – that force should have been directly transferred through already extended elbows to do the actual work of lifting the bar off the floor.

The next time you deadlift, think of holding heavy grocery bags at your sides. Your elbows should hang straight and heavy as you feel the tension stretch at elbow pits and wrists. There should be a sense of pre-loaded tension in your arms before you initiate the lift by pushing the floor away with your feet. Some of these points can be solutions to minor problems that you may have, and some could serve as new ways for you to approach a lift. Now that you are more aware of what the elbows can do to make your lifting experience better, I hope these tips can keep them injury-free and enjoyable through many of your PRs for as long as possible