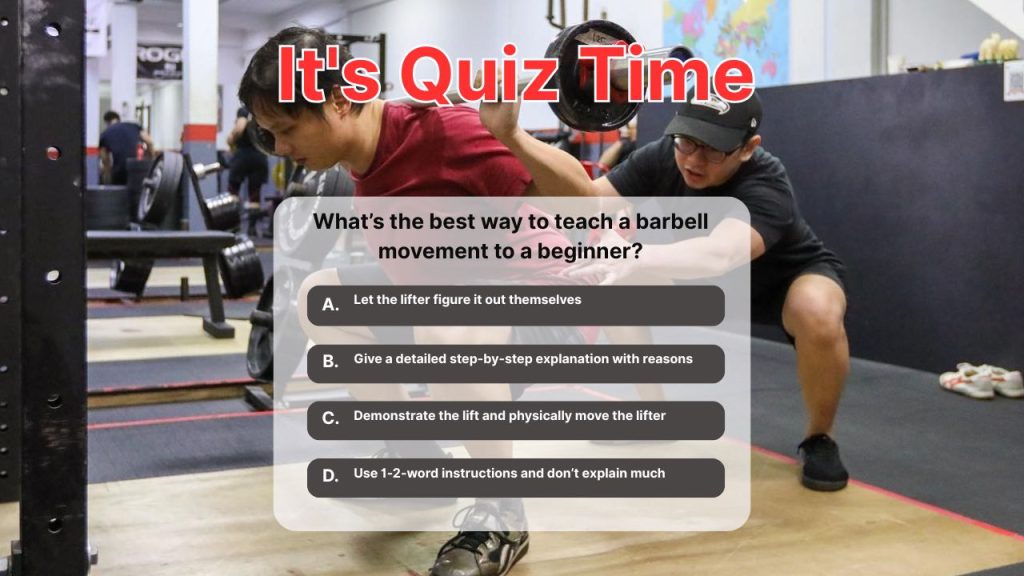

Question:

What is the best way to teach a barbell movement to a beginner?

A. Allow the lifter to practice freely first; everything will naturally self-organize

B. Give a full step-by-step explanation, including the “why” behind each step

C. Demonstrate the movement, then physically guide the lifter into the correct positions when needed

D. Don’t explain too much; use short, simple instructions and ensure the lifter follows them

At a quick glance, Option B probably sounds about right, huh?

Congratulations — you are wrong.

Let’s walk through why.

Option A: Let everything self-organise

This is the most hands-off approach. In theory, it sounds attractive: let the lifter explore, adapt, and discover their “own” technique.

There is a legitimate framework behind this idea, best articulated in Mike Tuchscherer’s writing on self-organizing technique. In that model, the lifter learns by interacting with constraints rather than by following constant external cues. Over time, they develop a deeper internal sense of what good movement feels like.

However, this approach has two major limitations when applied to beginners:

1. Beginners don’t know what “wrong” feels like yet.

Without boundaries or guidance, they may repeatedly reinforce inefficient movement patterns or bad form.

2. In-person coaching changes the equation.

Self-organising approaches are more applicable to advanced lifters or online coaching, where real-time intervention is limited. If someone pays for coaching — especially in person — they reasonably expect immediate professional input, not silence or reliance on what the client feels is right.

So while self-organisation is real and valuable, heavy reliance on it with a novice is a poor teaching strategy.

Option B: Explain everything

This is the opposite extreme – and by far the most common mistake.

At first glance, it feels like good coaching. The coach explains all the science behind the lift: every joint angle, every muscle action, and every reason behind each step.

To some lifters, this can sound impressive:

“Wow, maybe this coach really knows their stuff!”

But to a true beginner, it often feels more like this:

“Oh shoot… there are way too many things to remember.”

They might not say this to you directly, but if you start hearing them chanting a series of mantras — stand tall, move back, toes out, etc. — while trying to lift, that’s a good indication you’ve put too much on their plate.

Why does this happen?

Because when we hear the word teach, we subconsciously think about how we learned in school. In school, teaching is about understanding. If you don’t understand, you fail the test.

But movement learning doesn’t work like classroom learning.

In real life, we do many things well without understanding their mechanics, why they work, or how they work:

1. Walking

2. Riding a bike

3. Driving

Lack of understanding does not prevent competent execution.

Things get worse when, in a single one-hour session, a beginner is expected to learn:

1. A new movement pattern

2. New terminology and cues

3. New equipment in a new environment

4. Multiple technical concepts

We should be asking a better question:

Does every piece of information need to be taught on Day One?

The answer is no.

What should be taught on the first day?

Only the bare minimum information that the lifter can immediately act on.

Clear, simple commands that lead directly to better movement.

This brings us to the more effective options.

Options C and D: What Actually Works

Option C – demonstrating the movement and physically guiding the lifter — is often useful, especially early on. However, visual and tactile cues have limits, which we’ll discuss shortly.

Option D captures the core idea more accurately:

Don’t explain too much. Give short, simple instructions, and make sure the lifter follows them.

Yes – it can sound a bit like commanding a dog:

1. “Sit.”

2. “Hands.”

Or in lifting:

1. “Hip drive.”

2. “Knees out.”

And honestly? That’s not entirely wrong.

Early movement learning is about execution, not comprehension.

Why less is more (Pareto principle)

There is a clear law of diminishing returns in coaching communication.

If 10 short cues get a beginner to 80–90% accuracy,

then spending 20 cues with long explanations to reach 85–95% accuracy is usually not worth it on Day One.

This is the Pareto principle applied to coaching:

most results come from a small number of inputs.

More talking does not equal better coaching.

Verbal, visual, tactile – how do we choose?

All learning involves multiple channels, but they don’t contribute equally.

Verbal cues (primary)

Verbal instruction is usually the most practical:

1. The lifter doesn’t need to shift eye focus

2. Instructions can be delivered mid-movement

3. Think of it like listening to the radio — no visual shift required

Visual cues (supporting)

Demonstrations help reinforce verbal cues, much like subtitles reinforce dialogue in a movie. However, visual cues temporarily shift the lifter’s attention, especially if they need to look toward the coach.

Tactile cues (situational)

Physically placing a lifter into position can be effective for static positions, but:

1. It can’t be used effectively during dynamic movement

2. The lifter usually needs to be stationary

3. Under load, it can feel distracting or intrusive

Where self-organisation actually fits

While beginners shouldn’t be left entirely to self-organise, self-organisation is always happening internally.

The lifter isn’t memorising steps — they’re learning how the movement feels.

This is called proprioception.

Over time, with clear instructions and the aid of visual and tactile cues from the coach, the lifter starts to associate:

1. “That felt balanced.”

2. “That felt off. I need to…”

3. “This is good form.”

This internal feedback is what ultimately drives skill acquisition, but it needs structure early on.

Final Takeaways

For lifters:

1. More explanation from your coach does not mean better coaching

2. Understanding does not guarantee good execution

For coaches:

1. Information you give must be actionable, or it’s just noise

2. Your job is not to make the lifter smart — it’s to make them move correctly within your model

“The ability to simplify means to eliminate the unnecessary so that the necessary may speak.”

— Hans Hofmann